"The Legal Center Movement: Ten Years in Retrospect" (1961)

Author: Robert G. Storey

Source: American Bar Association Journal, Vol. 47, No. 10 (October 1961), pp. 997-998

Published by: American Bar Association Journal | Shared with permission.

CAIL Note: Due to the length of this article, it has been divided into seven parts. This is part 1/7, where Storey examined the trends of the legal center movement nearly a decade after the Southwestern Legal Foundation was founded.

Storey discusses the beginnings of the legal center movement and the rapid growth of the legal center concept in all parts of the country. He points out how important legal centers have become in the campaign to promote world peace through law.

Nearly a decade has passed since the completion of the first modern legal center. The purpose of this paper is to examine the current trends in the legal center movement as a part of the Survey of the Legal Profession; to supplement observations published in the Southwestern Law Journal in 1950;1 and to suggest certain practical principles concerning the organization of a legal center. The center movement has grown rapidly during recent years, and with current trends of increased interest and support it promises even greater achievements in the future.

In 1950 the main thrust of center activities appeared to be directed to ward answering the cry of the Bar for increased “how to do it” training of law students and for practical continu ing education for members of the Bar. At that time much was written attack ing legal education on the grounds of its impracticality. One for example said:

It should be noted that law is the only profession wherein the trainee is not accorded some practical foundation before he is “turned loose on society”. 2

Another had this to say:

The modern law school is composed of students with casebooks, a law library, classrooms and professors, but there is nothing approximately approaching a law office or a laboratory in which the student may learn to apply the law that he may have learned. 3

Criticism of professional competence and training was even more marked in the area of continuing legal education. This criticism was answered by increasing activities in very practical fields, primarily through institutes and publications. The practicing lawyer is exposed more and more to continuing practical education in the developing and changing fields of the law.

To determine how the legal center movement was progressing, a survey of American law schools was recently conducted as a part of the Survey of the Legal Profession. The reports of 112 law schools reflect a favorable increase in center activities. There is, in general, a continuation of the same overall objectives motivating the center movement in 1950, viz: improvement of standards of legal education, more “how to do it” training, increased legal research, and specialized training of practicing lawyers with the aim of improving professional competence.

In the 1950 survey, fifty of the ninety-six law schools reporting supported continuing education of members of the Bar, and thirty-nine schools had no program. At the present time sixty-six of 112 schools report a program of continuing education and only thirty-three report none. This increase seems very favorable considering the number of small schools with limited facilities and those remote from large population centers. The emphasis in continuing education remains geared to the needs of the practicing lawyer, although there is significant activity being directed toward the public responsibility of lawyers, for example, the Rule of Law movement. The typical institute may involve the law of taxation and have the discussion center around newly revised sections of the Internal Revenue Code, or the institute may involve a problem peculiar to the particular locale such as agricultural, mineral or oil and gas law. Such subjects as draftsmanship of legal instruments and estate planning typify the pamphlets and publications currently distributed among practicing lawyers.

The geographic distribution of institutes and other center activities is fairly uniform, and all sections of the country are represented. The Midwest and South appear to have the greatest amount of activity, while the Pacific Northwest is just now developing significant programs. The statistics do not reveal the significant success of institute programs. The fact is that most law schools sponsoring such programs have found them to be highly successful and popular with the practicing Bar. Attendance is reported generally to be good and many schools have expressed plans for substantial expansion of their institute programs both in number and scope.

[Sources as shared in the original article:]

1. The Modern Law Center, 4 S.W.L.J. 375 (1950).

2. Silver, Law Students and the Law: Experience-Employment in Legal Education, 35 A.B. A.J. 991 (1949).

3. Roberts, Performance Courses in the Study of Law: A Proposal for Reform of Legal Education, 36 A.B.A.J. 17 (1950)

About the Author

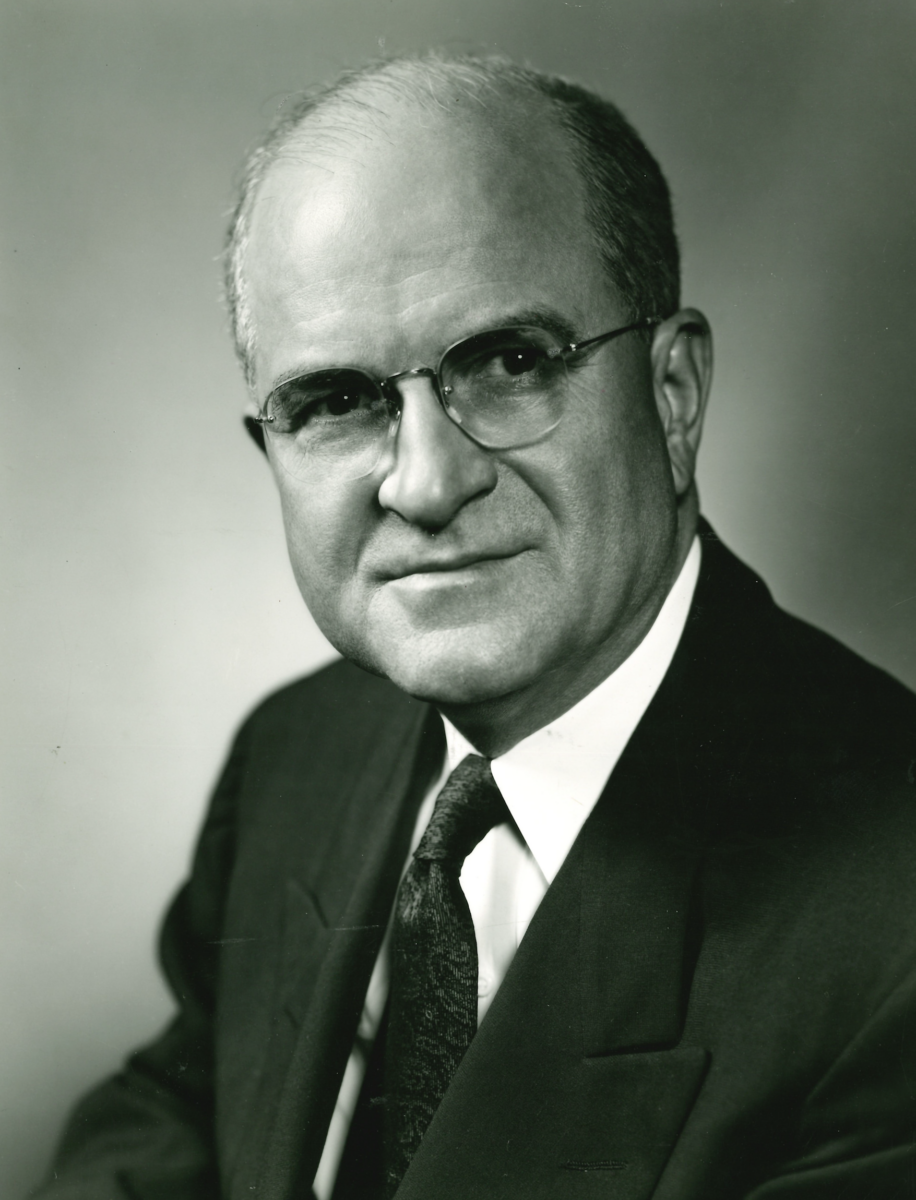

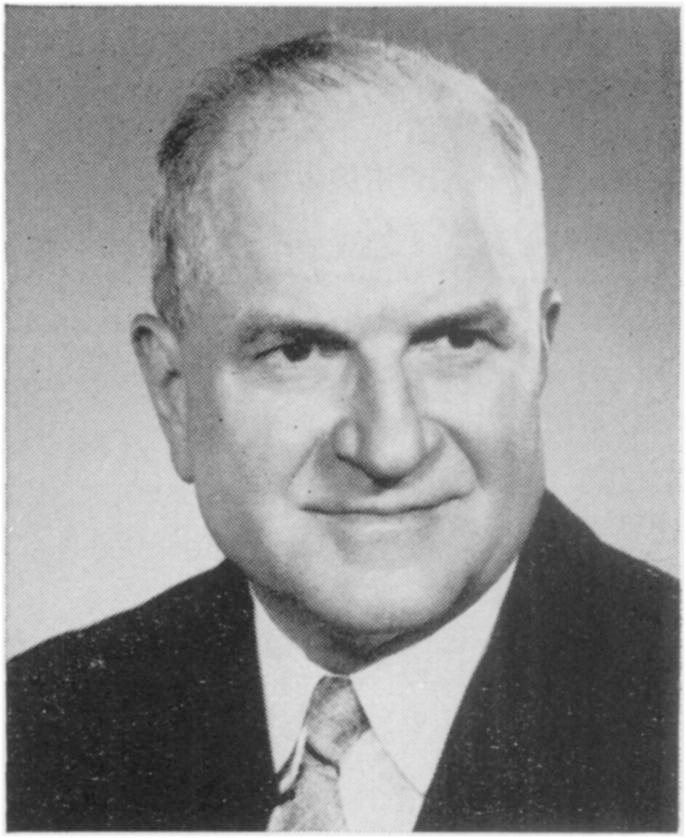

Robert “Bob” G. Storey (1893-1981) was the founder of Southwestern Legal Foundation, now The Center for American and International Law.

Storey was a prominent Texas lawyer whose illustrious legal career included being elected the president of the Dallas Bar Association, of the State Bar of Texas, and later of the American Bar Association.